Archive

Disaster sociology’s lessons on the US COVID-19 response

The field of disaster sociology, or the sociology of disaster, was born out of a need to understand the social impacts of a wide range of catastrophes and since its beginnings in the early 20th century, sociologists have been on the ground studying everything from earthquakes, terrorist attacks, and even the Exxon Valdez oil spill. The work has been vital in helping victims of disasters get back on their feet and has been employed by US government organizations like FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) and the U.S. Air Force (during the Cuban Missile Crisis). In fact, a good chunk of disaster sociology that’s available on the internet can be found on US government websites, especially FEMA’s website[1]. It is certainly easy to point out mistakes after the fact, but here are a few critical missteps in the US response to COVID-19 that may have been avoided if only we had paid more attention to what sociologists have been telling us for years.

We promise not to panic (as long as we have enough toilet paper)

“Individuals can deal with the truth of certain dangers more adequately than they can deal with misinformation which is later contradicted by experience.”

-Dynes et al, in a 1972 report[2] published by the US Government’s Defense Technical Information Center.

One key insight from disaster sociology is that although it does happen occasionally, disaster situations do not typically produce collective panic. This might go against what we’ve been taught by zombie movies where the living can be every bit as dangerous as the undead, but this sort of mass panic is a popular myth that has been repeatedly refuted by sociological research. This, in fact, might be the most well-known contribution of sociology in the field of disaster management. Unfortunately, it is a myth that public officials continue to use as the reasoning for their disaster responses, namely in decisions to not disseminate full, accurate information to the public. Whether the information is about the strength of an incoming hurricane or how infectious or lethal a virus is, people are better off if they know what they are in store for.

The need for trustworthy leadership driving unity

A study[3] done after the 1995 earthquake in Kobe, Japan found that a successful reaction to a disaster required the community to have a trust and a willingness to engage in mutually beneficial, collective action. People need to come together during disasters to successfully navigate them, and they found that this could be greatly facilitated by a trusted leadership dedicated to helping communities build consensus on what needs to be accomplished. In contrast then, policies that leave much to individual discretion without clear guidance may be harmful and counterproductive. COVID-19 provided us an opportunity to come together to combat a single, shared problem, and instead we became more divided.

Be prepared

In the early 2000’s, disaster sociology experienced a shift from focusing on what transpired after disasters to assessing our vulnerabilities prior to disasters, because, as David McEntire[4] puts it, “We have control over vulnerability, not natural hazards.” This included a call to understand where a population’s vulnerability lies as a whole as well as examining why some demographic groups may be more or less impacted by natural disasters (and pandemics) than others. The worst of a disaster could be mitigated simply by being prepared.

It has been common knowledge for decades that outbreaks of infectious diseases are as inevitable as hurricanes and earthquakes, but we were still “blindsided” by COVID-19. It is hard to speculate how different things would be if the National Security Council’s pandemic response team remained in tact, disbanded to save money in 2018, but our failure to be prepared was not only ignoring sociology but nearly every infectious disease expert on the planet. Much like the policy changes after the San Francisco earthquake in 1906 have long protected the city, perhaps the lessons we have learned in 2020 about how vulnerable we really are will help protect us, at least in part, from future outbreaks.

Lingering effects

Disaster sociology has shown that the aftereffects of disasters can cause lasting shifts in social structures, and these impacts can be varied and far-reaching. Hurricane Andrew resulted in an exacerbation of racial inequality and special segregation[5]. Hurricane Hugo led to an increase in marriage, birth, and divorce rates[6] in the counties it hit. The black plague of the 14th century is said to have ushered in everything from the Reformation to the Industrial Revolution[7].The media has had a lot to say about the permanent impacts of COVID-19, whether it is more online shopping or our nation’s youth never getting to experience the wonder of an all-you-can-eat buffet. Still, there is an opportunity to anticipate and position ourselves for these lasting changes. Some are easier to forecast—companies are already announcing permanent work-from-home policies. Others might not be so apparent. We are bound to have complex, social changes whether they be from the collective stress caused by COVID-19, the normalization of social distancing, or the mass disruption of our education system. Disaster sociology tells us that changes will happen. Social science research, if we are willing to listen, may give us insight into what the future might hold.

[1] https://training.fema.gov/emiweb/downloads/drabeksociologydisastersandem.pdf

[2] https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/750293.pdf

[3] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/255659714_Social_Capital_A_Missing_Link_to_Disaster_Recovery

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326983970_Tenets_of_vulnerability_An_assessment_of_a_fundamental_disaster_concept

[5] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242019211_Disasters_and_Social_Change_Hurricane_Andrew_and_the_Reshaping_of_Miami

[6] https://www.semel.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/publications/Mar%202002%20-%20Life%20Course%20Transitions%20and%20Natural%20Disaster.pdf

[7] https://gen.medium.com/how-the-black-death-radically-changed-the-course-of-history-644386f5b803

Analysis at Ethnographic Research, Inc.

Analysis is a sacred and labor-intensive element of our work at Ethnographic Research, Inc. Sometimes we hear about ethnography timelines that have reporting slotted just a couple of days after the end of fieldwork and we aren’t sure how that is even possible. Ethnography is about bringing people and culture to life; it gets to the heart of what’s really going on with a depth that is simply impossible to achieve in a couple of days. Good ethnography offers what Clifford Geertz called “thick descriptions.” More than just reporting some top of mind ideas, it goes much deeper into context and culture. To get there, we rely on (1) analytical rigor, (2) theory, and finally, (3) years and years of experience.

1. Analytical rigor

Doing analysis right takes a lot of work and a lot of time. We spend around six hours doing analysis for every hour of video we collect, and we collect tons of video. We often provide some “early insights” to clients who need something to work from immediately, but to do a complete analysis that makes the most of the data? That takes time.

Still, it doesn’t matter how much time you spend doing analysis if you don’t spend it wisely, so we use methods like Glaser and Strauss’s Grounded Theory, an inductive approach to analysis where data is coded and categorized until insights begin to emerge. People tend to picture analysis as this magical process where a wild-eyed, crazy-haired social scientist is thumbing through notes and watching video until some brilliant idea pops in their head. And yes, there are “Eureka!” moments (and sometimes crazy hair), but in reality, we follow fairly structured steps. If we didn’t, those big ideas might never show up and if they did, we wouldn’t be sure that they were trustworthy.

2. Theory

Our team is academically trained in ethnography, and we learned that using theory to help inform research is not only helpful, it is required. It just makes sense. Brilliant minds have been wrestling with similar topics for years. It would be silly not to take advantage of that, and although we’re all sociologists by training, we also use theory from anthropology, psychology, and sometimes economics and philosophy.

Our use of theory has a meaningful impact on our results. It is vital in making sense of data, and it helps so much in understanding the social and cultural drivers behind the behaviors we observe. Research that ignores culture comes out flat. For social scientists, by definition, if you want to understand people, you have to look at the society and culture they live in: the people they interact with, the institutions they are a part of, the information they consume, and any other outside influence that shapes the way they see the world. Theory provides the scaffolding for organizing and understanding all of that data.

3. Years of experience.

Ethnographic Research, Inc. opened its doors back in 2001, long before the iPhone, long before Facebook. Back when we started, ethnographers didn’t do in-homes, they did in-caves.

We’ve been observing people in-context for nearly twenty years, and we’ve picked up a few things along the way. This gives us a leg up whenever we start a new project—we go in with a strong understanding of how households have evolved over the last couple of decades and can use this to give projects an analytical jumpstart. We can approach new topics with a certain maturity and sophistication that would have been impossible were we just starting out. For instance, we do a lot of work studying how illnesses impact people’s daily lives. We’ve studied the daily lives of people with cancer, heart disease, arthritis, chronic pain, lupus, epilepsy, and many others. When someone comes to us wanting to learn about the patient experience of a condition we haven’t studied, like multiple sclerosis, we have all of this past work to help us learn, right away, what is unique and different about living with MS.

This experience is just as helpful for our other projects too. We have years of experience watching people shop, work, cook, groom, clean, play, parent, travel, and more. This allows us to place our research topic into a much larger database of insights into daily life habits and rituals. It helps us in every aspect of the journey that is ethnography. We can avoid common pitfalls in sampling and recruiting, we can get the most out of our in-home visits, and our analytical processes are refined and streamlined. We have also learned that it is our analytical processes that add the most value for our clients. All of the time and rigor we give to analysis are absolutely necessary when your research aims for deep, rich insights.

Some of our favorite theories for doing ethnography in health care spaces

At Ethnographic Research, Inc., we always emphasize the value of social theory in ethnography and its ability to add depth and nuance to our results. It is like having the ghosts of sociology’s past prodding us to consider looking at our data this way or that way, just in case there might be a big insight around the corner. Research for the health care industry is no exception. In fact, given how challenging in-context observations of health care settings can be, it’s a crying shame not to make the most out of that data. That’s where theory lend a hand. There is a ton out there, but here are a few theories we tend to use the most:

Stigma: Emile Durkheim, Erving Goffman. Stigma is an essential variable to consider when we do projects on living with an illness. Sometimes the stigma is the result of the physical effects of an illness, its accompanying behaviors (like injecting insulin in public), or by just having the illness (like a sexually transmitted disease). The impact of stigma can be as traumatic as the physical effects of the illness itself, and Durkheim and Goffman helped us understand these dynamics.

The sick role: Talcott Parsons. Talcott Parsons’ functionalism hasn’t necessarily stood the test of time, but we still use his idea of the “sick role.” The basic notion is that when we’re deemed “sick” and take on the “sick role,” we’re excused from normal responsibilities while also being required to work towards getting better. For us, we often use it more broadly in examining how having a specific illness impacts a person’s social roles and their engagement with the world around them. Given our long history of studying different conditions, we can then compare the “sick role” of X illness with the many other illnesses we’ve studied in the past.

Gender theory: Simone de Beauvoir. We always make sure to attend to how gender roles impact the interactions and behaviors we observe. You could pick many influential gender theorists, but de Beauvoir was one of the first to draw the line between sex and gender, and this idea of the social construction of gender is arguably the fundamental starting point of most or even all current gender theory.

She also wrote that women and their bodies were the “inessential other,” deemed both alien to and lesser than men and men’s bodies. We can see this in women’s experiences of health care. In a study we did on a rare, difficult to diagnose illness, women, in trying to find out what was going on with them, weren’t taken seriously by the HCPs. Their physicians downplayed their symptoms as “just stress” or “just needing to lose some weight” when they had a condition that would be fatal if left untreated.

Presentation of the self: Erving Goffman. Goffman is back for a second round! For Goffman, when we interact with others we act, as if in a play, and our choice of words and our body language are designed to convey a certain image to the person we’re interacting with. This concept is essential when trying to decipher the interactions that patients have with their health care providers. It helps us make sense of how both sides communicate and how those communications are interpreted, which ultimately shapes treatment decisions and patient outcomes.

These interactions usually play out in the exam room, what Goffman would call the “front stage,” the stage that our clients tend to be most interested in. We always argue that we should also observe the “backstage,” their offices, labs, and break rooms, to see what HCPs are doing outside of direct patient care, to see how they interact with other staff members, and to get the entire picture of what’s involved in their day’s work.

This front stage and backstage distinction of Goffman’s is also important when we study the experiences people have with their illnesses away from the doctor’s office. It’s our job to understand how the public face of someone’s experience of an illness might differ from the private, backstage experience they keep to themselves or just share with their closest friends and family. It is often only in this backstage space where we can see what’s really going on.

The quantified self: Deborah Lupton. Just so we can include something from this century, the quantified self has become a more influential theory in the last couple of years in both our health care research and our technology research. It basically explores how we are increasingly measuring the wellbeing of our bodies with numbers. The most common example is fitness tracking (e.g., FitBits and Apple Watches), but you can see it elsewhere, like assessing diabetes status through the numerical output of a glucometer.

The quantified self can be considered a kind of extension or offshoot of the “medicalization of society,” another valuable theory from the previous century, the 70’s. It contends that more and more aspects of our lives are falling under the umbrella of medicine. A classic example of medicalization is giving birth. Where once done with family in the comfort of the home, now having babies in hospitals is the norm. Medicalization comes up periodically in our research too, like a project we did on Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS). Our participants’ friends and family didn’t take RLS seriously; they didn’t believe it was a real condition (rather the result of the medicalization of society). This led our participants to feel the stigma of having a “fake” condition and it impeded their ability to take on the sick role.

Often we combine these theories in our quest to understand and organize our fieldwork, our analysis and our reporting. What are some theories you love to use in your work?

Sociological Theory Comes to Life

When I was earning my undergraduate degree, there was a required class called Sociological Theory. The first time I became aware of the class was when a bunch of my classmates were sitting around, talking about what they were going to take the next semester. They all agreed to avoid Sociological Theory as long as possible. None of them WANTED to take the class. They said it was boring, difficult, and essentially a waste of time. It sounded awful. So, I put the class off too (even longer than statistics). When I couldn’t put it off any longer, I enrolled in the class. Boy was I surprised. I LOVED the class. It was interesting. And so useful.

Imagine that you are trying to solve a difficult puzzle without a picture of what it looks like. You are having trouble getting started. But then suddenly the outer edge of the puzzle comes together and you begin to see how the inside might look. Social theory often provides that type of tool for ethnographers. It gives us a framework or a starting point to organize data or to understand a pattern.

I’m a little bit of a social theory junkie and I’ll admit that sometimes, for fun, I take random experiences and try a few different social theories on for size to see how well they can explain what I have seen. It is very interesting to see how a single event can be understood in a variety of ways. Admittedly, some social theories have more explanatory power and a wider scope of applicability than others. One of my favorites is social exchange theory. You know this one. The premise is that all social relationships are based on exchanges between people and that these exchanges are based on a careful cost/benefit analysis of what each party is getting/receiving. This particular theory is widely applicable and explains a great deal.

A few years ago I saw this theory in action when I was asked to help a client understand the lives of women at high risk for HIV infection. I was spending time learning from a group of women who worked in the sex trade industry, hearing their stories, and learning more about how sex and protection fit into their work lives as well as their personal lives. It was during these conversations and afterwards during analysis that I saw social exchange theory at work. Many of the women I talked to summed up their decisions to not practice safe sex in terms of the costs and benefits they paid and reaped from their sexual exchanges. It turned out that NOT using condoms helped them to shift the power balance of the exchange in their favor. Obviously, at work they could demand more money if they didn’t use a condom. But less obvious was the exchanges that they often made in their private relationships. Not using a condom during sex with their significant others signaled trust, which was an important commodity that they paid into the relationship bank. Using a condom would signal lack of trust and would put them further into the negative when it came to power within the relationship. Although this seems counter-intuitive (i.e., using a condom SHOULD and does generally increase the power position of the woman), within this particular population, there were other, contextual variables at play that impacted the exchange. For example, among this population, there was not a surplus of eligible partners and every potential partner entered into the relationship in a one up position, just by virtue of being scarce. Also, there were cultural biases that made ‘cheating’ normal for men, but unacceptable for women. Cheating was something that female partners were expected to not only accept, but essentially pretend not to see. If they asked their partner to wear a condom, they were violating the agreement by pointing out that there was anything to be concerned about. Finally, because their partners could usually leave the relationship and more easily find a replacement partner than they could, the value of ‘more pleasure’ that not using a condom provided allowed my participants to add another benefit to what they were paying into the relationship.

Social exchange theory provided a framework by which to organize the data and to explain the seemingly counter-intuitive and self-destructive behavior that my participants reported. It also encouraged me to try to understand the motivations for their decisions from a more rational perspective based on their social and cultural context. Although I didn’t spend enough time in the field to really know whether the patterns I saw would be trustworthy in a larger population, social exchange theory provided a very interesting potential explanation for risk-taking behavior within this population and one that would probably indicate less traditional approaches to sex education and STI prevention efforts.

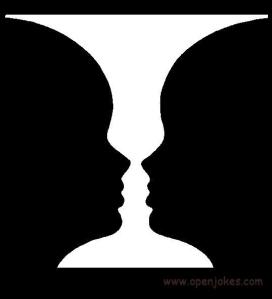

Reconstructing Reality: What do you see?

Social scientists and philosophers have been arguing about ‘reality’ for a while now. There are generally two approaches to how reality is understood and measured by social scientists. Those taking a positivistic approach believe that although people may ‘see’ things differently, there is an objective reality. On the other hand, those taking a phenomenological approach assume multiple realities to any given situation. As an ethnographer, I generally skew toward the phenomenological viewpoint. I realize that not all versions of reality hold up equally well, but I have seen many instances of people creating their own reality around their experiences and around products/services.

Social scientists and philosophers have been arguing about ‘reality’ for a while now. There are generally two approaches to how reality is understood and measured by social scientists. Those taking a positivistic approach believe that although people may ‘see’ things differently, there is an objective reality. On the other hand, those taking a phenomenological approach assume multiple realities to any given situation. As an ethnographer, I generally skew toward the phenomenological viewpoint. I realize that not all versions of reality hold up equally well, but I have seen many instances of people creating their own reality around their experiences and around products/services.

I usually use the classic film ‘The Gods Must be Crazy’ to help illustrate this concept. So, in the film, there is a pilot that is flying over the Kalahari Desert and he drinks a coke and then throws the bottle out of the window of his plane. A man named Xi finds the coke bottle and assumes that it is a gift from the gods and he and his tribe find TONS of uses for the bottle—it is a tool, it is a toy, it is a musical instrument, etc. In other words, they construct an alternate reality around the bottle. And so the movie is a parable to illustrate how one man’s trash can become another man’s treasure.

This is one way in which the social construction of reality comes to life in my work. I do see many instances of people finding all kinds of interesting (but unintended) uses for products. They might fashion an expensive piece of electronic equipment into a workbench or they might use a medical device in ways that are not consistent with instructions, but which fit better into their particular needs. In these situations, my job becomes one in which I help my client understand not only WHAT they are doing, but WHY. This often requires me to walk a delicate line. Generally, my client has given a lot of thought to design and they have created a product that does what it is designed to do pretty well. However, sometimes I have to help them understand that it isn’t all about what this product does. Sometimes it is more important to understand the social world in which the product lives and how their vision of what the product should be might not be consistent with the reality in which the product lives.

For example, many years ago, we were hired by a manufacturer of high-end electronic equipment. This company had given A LOT of thought to their product line and were really, really proud of all of the bells and whistles their products had. But after spending a few weeks in the field, observing and talking to the people who used their products, I realized that the bells and whistles were not only NOT appreciated by the customers, they were often feared! Many consumers lived in constant fear that someone else would change some of the settings on this device and then they would have to spend hours trying to figure out how to reset it. There was clearly a disconnect in the ‘reality’ of what this thing was and especially around what the expectations of it were. For my client, the real VALUE of their product and what they believed really differentiated their brand from others were the bells and whistles (this was evidenced by their advertising, but also by the angry response we got from designers and engineers when we presented our findings)! But for the consumer, the value of the thing was that it turned on when it was supposed to and allowed them to do their job without being too complicated or distracting them from their real task.

As I said before, not all versions of ‘reality’ are tolerated equally, but it does pay to try to understand how your product might fit into the reality of daily life and how your customer might be constructing their own story about exactly what your product is and especially how (and for what) it is valued.